Berlin Horse: Brian Eno and Malcolm Le Grice

July 9th, 2011 by HgBrian Eno’s earliest publicly available recorded work is the soundtrack to Malcolm Le Grice’s Berlin Horse (1970). Berlin Horse was Malcolm Le Grice’s first full-length experiment with the manipulation of film images, for which he combined a sixteen millimeter black-and-white film of his own footage showing nothing but a horse being lunged with fragments of The Burning Barn (1900) by the important British film pioneer Cecil Milton Hepworth.—from More Dark Than Shark

A Tale of Two Architects: Upjohn & Cram in Carroll Gardens

October 8th, 2010 by HgBilled as “the largest architectural event in the United States,” Open House New York Weekend is this Saturday and Sunday, October 9th and 10th. Landmark buildings of historic architectural importance all over the five boroughs of New York City will be open to the public for viewing each day. Among Brooklyn’s architectural wonders participating in the Open House event will be St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in Carroll Gardens, situated on the corner of Clinton and Carroll Streets.

Originally designed by Richard M. Upjohn (1828-1903), St. Paul’s was built in the Gothic Revival style popular during the 19th century. (R.M. Upjohn and his father also designed Brooklyn’s Greenwood Cemetery Gate, just a few miles away in Sunset Park). After a fire damaged the church, Ralph Adams Cram (1863-1942) was commissioned to redesign the interior in 1907, and this is where the story gets interesting: Cram is noteworthy among early 20th century architects for his resistance to the overwhelming current of early modernism. He’s been referred to by at least one writer as the “high priest of American Neo-Gothic,” in deference to his passion for pre-renaissance, medieval, Gothic architecture.

An agnostic in his youth, Cram underwent a dramatic spiritual conversion during a Christmas Mass in Rome and subsequently became a fervent Anglican—in fact, the Episcopal Church has honored Cram, along with Upjohn and John LaFarge, with a special Feast Day on the liturgical calendar, December 16. St. Paul’s, an Anglo-Catholic Episcopal church, is the only place where the work of these two important architects, Upjohn and Cram, is layered together within a single structure. Along with his writings on Religion, Art and Architecture, Cram is also the author of a book of ghost stories, Black Spirits and White.

“Gothic is less a method of construction,” Cram once suggested, “than it is a mental attitude, the visualizing of a spiritual impulse.” In the early twentieth century, this kind of attitude went against the grain of the growing, dominant trends of Modernism with it’s trenchant iconoclasm and absolute disdain for anything that valued a sense of continuity with the past. Cram’s sense of history and place, his embrace of mystical philosophies and eloquent theological musings on the nature of art were simply out of place in the cultural milieu that eventually gave us Frank Lloyd Wright’s Guggenheim Museum or the austere, curtain-walled designs of Mies van der Rohe’s glass box buildings.

The following information comes from St. Paul’s Press Release for the 8th annual Open House New York Weekend:

“On Saturday, October 9th from 11 am to 5 pm, there will be ongoing guided tours and self-guided tours in conjunction with “openhousenewyork.” On Sunday, October 10th, there will be an Organ Recital by St. Paul’s Music Director, Andrew von Gutfeld at 1:30 followed by guided tours and self-guided tours from 2-5 pm. Naturally, the parish welcomes everyone to Sunday’s 11 am mass.

“St. Paul’s has a rich history that dates back to Brooklyn’s pre-Civil War era, having been founded in 1849 by Irish Protestants, an often overlooked but important early New York emigrant group. In 1866, the parish asked R.M. Upjohn to design its church, which celebrates the Gothic Revival architectural style that was so popular in mid-nineteen-century America.

“In the decades following 1874, the year St. Paul’s Church was consecrated, the parish faced an identity crisis, with many of its original families having moved away, uncomfortable with Brooklyn’s increasingly non-protestant feel. However, the parish ultimately adopted Anglo-Catholicism, a popular reform movement that combined medieval ritual and community service.

“During this time, the parish commissioned prominent architect Ralph Adams Cram to redesign St. Paul’s interior, after a fire damaged the church in 1907. Cram, who designed the nave at St. John the Divine in Manhattan, gave St. Paul’s interior the Neo-Gothic flavor that it retains today.

“It is important to note that St. Paul’s enjoyed a racially diverse congregation since the 1920s, as it attracted members of Brooklyn’s West Indian community, who worked mostly as servants for wealthy families in Brooklyn Heights. Irving King, a current parishioner of West Indian descent, said his mother liked St. Paul’s because it was the first church where she was not “told where to sit.” This was at a time when segregation in many churches was the norm, when even the taking of communion itself was a segregated act—but not at St. Paul’s.

“Like Brooklyn itself, the church has always changed with the times and reinvented itself, welcoming newcomers in the last twenty years who have gravitated toward an increasingly gentrified Carroll Gardens and Cobble Hill. St. Paul’s today attracts a wide range of people from a range of different ethnic and socio-economic backgrounds, drawing in many young families new to the neighborhood. ”

Click on an image to enlarge:

The Temple of Blooom at Cinders Gallery

August 8th, 2010 by HgThe Cinders Gallery on Havemeyer Street in Williamsburg is just closing out one of the more amazing shows of the summer today—The Temple of Blooom is an installation of drawings, paintings, collage and sculpture. There are too many good things in this show to give an exhaustive description of what’s going on in the space; that such an engaging, inspiring installation could be assembled in the relatively small confines of a storefront gallery is testament to the vibrant energy that runs through the Brooklyn art scene, even during the Dog Days of summer.

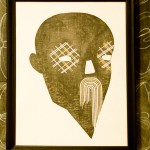

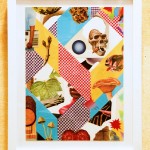

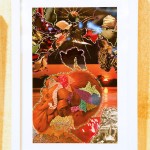

Hisham Bharoocha has put together a group of collages that resonate at once with 1960’s San Francisco psychedelic poster art and the dreamlike imagery of Joseph Cornell, or the poignant poetics of the late Joe Brainard’s collage work. Kelie Bowman’s delicately rendered drawing of flowers arranged in the shape of human forms might easily have been included in this year’s Biennial, across from Aurel Schmidt’s Arcimboldo-esque Minotaur drawing as a counterpoint to some of the Biennial’s brooding pessimism. The entire gallery has a magical, ritual-like atmosphere, as if one had walked into the after-effects of a Vodun rite. The black and gold painted papier mache shrine to “the gods of plants” by an artist who calls himself Sto, and John Orth’s mask-like drawings of disembodied, abstract spirit-faces further enhances the mysteriously evocative atmosphere of this show.

Photos and video from Friday’s musical performance by Inferior Amps, Noveller and Brian Chase are on the Cinders Gallery blog, along with pictures from the closing party tonight.

Click on an image in the gallery to view a larger photo:

Please visit more of Harold’s Sketchbook @ www.haroldgraves.com

Henri Matisse at MoMA, Drawing on the F Train

July 27th, 2010 by HgIt’s been so hot and humid in New York this month that I’ve just been carrying around a little pocket sketchbook with a pencil and a pen to do light drawings with. No book bag to carry on the train or my bike!

This last Monday I took the F train up to MoMA, and did some drawings on the way. I didn’t think I’d get in to see the Matisse exhibit—they’re doing a timed-ticket entry to help facilitate the crowds—but after seeing the Picasso Variations exhibit again and the Alternative Abstractions show, I took the escalator up to the Tisch gallery on the sixth floor anyway; it was already after five o’clock, and traffic was light enough that they were allowing folks to walk through. What a treat: I had several of the galleries practically to myself while the guards were winding things down for closing time.

I’ll go back for another visit, but for now my favorite things were the little line drawings done on paper, some of them not much bigger than a matchbook, and the large Bathers by a River from the Chicago Art Institute.

I made this little Flash Movie from some of the pages in my sketchbook—all done with rapidograph pen and pencil. Some of these are subway riders, others are quick sketches copied from Matisse.

Current Studio Work: Egg Tempera Painting

July 8th, 2010 by HgI started working on another egg tempera panel last month, based on one of my sketchbook drawings. I scanned this in last night after working on the background. Right in the middle of the heatwave, it was so warm in my studio (92°F!), the egg medium started to congeal in the jar, so I decided to stop working for a while. I’ve got more work to do on it, but sometimes it’s interesting to see a panel in an early state.

St. Mark’s Bookshop Poetry Reading Series at Bar 82: Geoffrey Nutter & Dorothea Lasky

April 30th, 2010 by HgThe Saint Mark’s Bookshop Poetry Reading Series was held at Bar 82 tonight. Geoffrey Nutter and Dorothea Lasky are two wonderful, amazing poets who each read from their recent work. Mr. Nutter read from Christopher Sunset, and Ms. Lasky read from Black Life, both recently published by Wave Books.

The Forest of Images: Recent Exhibitions

April 13th, 2010 by Hg“The whole visible universe is only a storehouse of images and signs to which the imagination assigns a place and a relative value; it is a kind of nourishment that the imagination must digest and transform.”

“Nature is a temple in which living columns sometimes emit confused words. Man approaches it through forests of symbols, which observe him with familiar glances.”

—Charles Baudelaire

Symbolism, both as a movement in poetry as well as painting, is often said to have its source in Baudelaire’s writings. I suppose one could argue that this notion is a bit of inherited, modern European chauvinism, and that one might just as easily trace the origins of all symbolic expression to the cave paintings and petroglyphs of Cro-Magnon people living in the Dordogne 40,000 years ago. But for the purpose of reflecting on contemporary painting practice as it happens now, Baudelaire is just as good a jumping-off point as any. Depending on what historical scheme you want to follow, after Baudelaire comes Stéphane Mallarmé, then Paul Gaugin, and from there the trail branches off into a wilderness of groups, movements and characters, all clamoring for their place in the modern story of poetry and painting, in all its manifold expressions.

Nearly a century and a half separates us from Baudelaire now, and the forest of images has grown up around us, a vast expanse of confusion and promise. Where do these images arise from, and where do they go? The Romantic poets and their Symbolist heirs asked this question, and in their attempts to answer they gave the world Van Gogh and Gaugin, Wagner, Nietzsche, and Freud. When the Dadaists asked these questions they gave rise to Surrealism. Perhaps it was Warhol who joked that when late twentieth-century modernism asks these questions, they get the internet, along with a raft of corporate logos and advertising as a response; but Andy Warhol died before the internet came into being, so it probably wasn’t him. Compared to Baudelaire’s Paris, or the Dadaist’s Zurich, the 21st century metropolis is a whirlpool of commercial images in constant, swirling motion. Be that as it may, it seems as if the post-modern art spirit continues to ask, Where do we come from? What are we? Where are we going? Even when it seems that the only answers coming back are network sound-bites, YouTube clips and corporate pornography, the questions persist.

∞

The Bruce High Quality Foundation’s installation at the Whitney Biennial, We Like America, and America Likes Us is a darkly humorous elegy for a culture that is so deep in decline it appears to be coming apart at the seams. A white Cadillac ambulance is parked on the fourth floor of the Whitney in a room by itself, headlights shining against a blank wall, white curtains drawn over the rear windows, the driver’s side and passenger windows painted black. On the windshield, from somewhere inside the vehicle, a continuous looped video is projected, so that the ambulance has been transformed into a kind of movie theater. The video is a long montage of YouTube clips from familiar film and television broadcasts, presented in a documentary style, as if Ken Burns were giving an overview of late twentieth-century culture in a series of short snippets.

The framing device of the ambulance itself is actually where the video loop begins: a scene from Joseph Beuys’ important 1974 performance, the sardonically titled I Like America, and America Likes Me. Beuys arrives at JFK airport wearing his iconic felt fedora and fishing vest, disembarking from the plane with his hand covering his eyes; he is met by a pair of assistants who immediately wrap him in a gray felt blanket and load him into the back of a Cadillac Miller-Meteor ambulance, almost identical to the one sitting in the museum. We then see the white vehicle, with lights flashing, rushing through traffic to arrive at the René Block gallery in Manhattan, where Beuys will spend the next several days alone in a room with a coyote—an animal of symbolic importance in much of Native American mythology.

Beuys’ performance has been discussed at length elsewhere, so I will just mention here that after establishing some rapport with the animal over 3 days he embraced the coyote and then left New York City the same way that he arrived, being carried to JFK in the back of the ambulance, later explaining “I wanted to isolate myself, insulate myself, see nothing of America other than the coyote.” It happens that the Cadillac Miller-Meteor ambulance is also commonly used as a hearse, and this dual function of the vehicle forms part of the poetic irony of the Bruce installation; a female voice narrates a long, rambling, narrative-poem in which America is eulogized as a person who has recently died, or perhaps a lover or spouse who has been separated. The ambulance that carried Joseph Beuys to commune with the Native Spirit of America has now become a hearse, presumably with the dead corpse of America lying concealed in the back, the ghost of our collective fantasies about “America” flickering on the windshield in a late-night television rerun with the sound turned off. For me, We Like America, and America Likes Us is the most potent piece in this year’s Biennial; in it’s satiric way it establishes a theme that runs throughout the rest of the exhibits; even the choice of having a female narrator for the voiceover seems significant, as much of the strongest work in the rest of the show is by women.

∞

So here is my list of notables from the Whitney Biennial: the Bruce High Quality Foundation is a collective of anonymous artists, each of them named “Bruce;” after that, Nina Berman, Dawn Clements, Hannah Greely, Josephine Meckseper, Erika Vogt, Sharon Hayes, Aurel Schmidt, Kate Gilmore, Maureen Gallace, and Julia Fish, in no particular order. Four video artists, two painters, two drafts-women, a sculptor and a photographer, plus the Bruce installation.

Josephine Meckseper’s video, Mall of America, continues the critique of American cultural identities—a long, slow-motion video shot with color filters in a large, sprawling shopping mall, with an ominous, droning soundtrack. The combination of slow-motion, saturated color and menacing ambient sound transforms the commonplace environment of a suburban shopping center into a nightmarish underworld. In one sequence a Hollywood war movie is playing on a flat-screen TV behind a glass display case, and the camera zooms in until we are momentarily “inside” the movie which is playing inside the Mall—a simple but effective way to conflate the theater of “actual” warfare with Hollywood and the pervasive consumer culture that the Mall-space represents.

Kate Gilmore’s Standing Here is a claustrophobic video installation: watching the artist punch and kick her way out of the narrow confinement of a sheet-rock cubicle is made more visceral by the fact that the actual space she shot the video in is right there in the room, next to where the video is being projected. As I was standing there watching Gilmore—who is wearing a red dress with white polka-dots—kick and tear at the confining walls, I heard several of the people with me remark how uptight and claustrophobic it made them feel. The gray, silo-like cube is of course intended to be metaphoric of repressive patriarchal structures that confine and challenge women—but I suppose it could also be symbolic of forces or ideas that can confine and limit any of us, whether those forces be patriarchal, political, aesthetic, or even “feminist.”

∞

- “Angel T” by Tourya Othman

- “Sacre (Homage to Michelangelo Galliani)” by Michela Martello

- “Courage (detail)” by Michela Martello

- “Cuore” by Michela Martello

- “Last One” by Michela Martello

- “Venus” by Michela Martello

Michela Martello and Tourya Othman are two artists currently exhibiting at the Tria gallery, in a show entitled Idols and Icons. Working in a symbolist mode of representation, both artists create paintings derived from the imagery of traditional religious and spiritual iconography. Othman’s paintings of cherubic “angel heads” put one in mind of the Baroque paintings of Georges de la Tour with their open-mouthed depictions of ecstatic rapture and numinous awe in bold chiaroscuro—but with the introduction of a surreal chromatic intensity that is reminiscent of the Chicago Imagist painter Ed Paschke, or even some of the later, hallucinogenic realism of Salvador Dali.

Martello’s five canvases draw on historical, religious imagery from both Eastern and Western culture to create a personal symbolism—images of Italian sculpture and Latin American folk art as well as Hindu and Buddhist depictions of bodhisattva-like figures. There’s a certain lightness of touch and handling of paint that reminds me of recent fresco paintings by Francesco Clemente. But the personal symbolism and feminine concern with identity also makes one think of Frida Kahlo or Leonora Carrington—two artists whose work is in the spirit of Baudelaire’s Symbolist ideas. Courage features the truncated form of a standing warrior brandishing a sword in the manner of a Hindu or Buddhist ceremonial court figure, while the kilt worn by the bodhisattva-like guardian has numerous nude female figures painted on it, each of them situated in various states of repose upon a pink field. The alluring, relaxed eroticism of the small dakini-like women combined with the masculine solidity and strength of the sword-wielding figure is a compelling combination of opposites.

Perhaps it is appropriate that Cuore, a small square painting of a red heart with the aorta severed and a small yellow tiger standing in the middle, is situated on a blue field directly above Courage. The courage and open-heartedness that is required to be an artist in a world obsessed with confining formalist structures, as Kate Gilmore seems to be suggesting in her work at the Whitney? Or, perhaps more specifically the courage to be a female artist in a milieu that is traditionally dominated by men. I think Martello is too intelligent of an artist to allow herself to be confined to any one of these meanings. A friend who is deeply involved with esoteric Buddhist practices has suggested that the image could simply be evoking the courage to remain an open human being, working with the forms that one has inherited from one’s culture while remaining free from their limitations. In any case, Cuore with it’s little tiger in the center and the suggestion of gratitude as an antidote for anger and greed is possibly my favorite painting in the show, along with Last One, a painting of fifteen miniature Christmas decorations that the artist sketched while traveling in Ecuador. This is the painting that most puts me in mind of Clemente with its lightness of touch, gentle naiveté, and suggestion of mystical portents. Each figure is delicately rendered, as in an old illustrated catalog of children’s toys, and is floating against a seemingly empty field of raw canvas. As in the best of Clemente’s work, there is a mystery in the presence of the figures that escapes explanation.

∞

“No ideas but in things.”—William Carlos Williams

As I was preparing to work on this entry, an advance copy of Christopher Sunset, the new book of poetry by Geoffrey Nutter, arrived in the mail. Mr. Nutter is one of those rare poets who, like John Ash or Pablo Neruda, is possessed of a genius that simultaneously opens out towards a field of mystical imagery—laden with the possibility of transcendence—while remaining firmly grounded in the matter-of-fact, stubborn currency of the everyday, the here-and-now.

A poem by Mr. Nutter entitled Thanksgiving declares:

I’ve been puzzled long enough

by modernity and its poems.

It’s evening. I’m walking down

to the river to watch the sun set.

The clouds are like millions of bright blue leaves

scattered across the sky.

I’m sitting in the shade of a massive tree

but the shade is alive. And under the sunset

the giant gray trestles of the bridge.

And under the bridge, and nearer to me,

shards of bottles and the gravel

of the down-at-the-heels marina,

its broken-down boathouse, the gray

cinder blocks in the weeds, an overturned

boat, a length of black tubing.

It’s all coming together now.

It’s the sky and the earth, resting together

in the unassuming darkness.

—Thanksgiving, from Christopher Sunset, ©2010 by Geoffrey Nutter, published by Wave Books

∞

Visit my website at www.haroldgraves.com

Shamans and Showmen: Poetry Reading @ Concept V

April 3rd, 2010 by HgDavid Dunlap at CUE Art Foundation

January 8th, 2010 by HgNote: please click on an image to view a larger photo, then click that photo to get even larger:

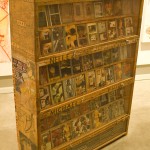

Notes on David Dunlap at CUE

The CUE Foundation is showing the protean work of Iowa City artist David Dunlap in their Chelsea gallery on west 25th street. This is an installation by an important and influential artist who has been deserving of larger recognition, at least in the New York art community, for a long while.

For the past four decades artist David Dunlap has been keeping a series of daily notebook journals and sketchbooks–a kind of stream-of-consciousness diary of daily life and reflections on art and the world, which he presents in various formats, each one showcasing a different incarnation of the artist’s ongoing work.

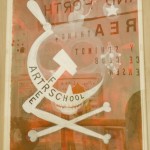

Empty, luminous, dream-like, ungraspable and mysterious: the current exhibition, Mr. Dunlap’s first solo show in New York City, has as its centerpiece a section of a fifty-foot high plywood house the artist constructed in his back yard in Iowa City. Inside and around the “house” are numerous hand-made book-cases displaying the many notebooks, sketchbooks and project-scrapbooks that have continued to accumulate like deposits in an ever-expanding coral reef of memories, dreams and doodles. In the middle of the house is an enigromatic object: A Device for Detecting the Presence of Martin Luther King, Jr. Along the walls of the exhibition space are displayed individual, framed drawings–many of them small pages pulled from the ubiquitous wire-bound notebooks Mr. Dunlap carries with him, while others are larger-format drawings, often executed with a ball-point pen: homemade calendars illustrated with abstract doodles and mysterious shapes. Most any mundane, ordinary event becomes the jumping-0ff point for long, meandering riffs on various fantastic and often funny drawings–abstract patterns that morph into figures and symbols which populate the daily calendar of a life lived with friends and family. Enigmatic phrases headline and punctuate the sprawling installation of imagery: Dreaming, He is At Work, Hitler Dream Analysis, Give Us Back Our Flag You Waterboarded, This is Always Finished, Free Art School!

Egolessness and equanimity are seemingly rare in our world, and this is particularly true in the New York “Art World” where egos are often large and tending towards the loud and self-important. The spirit of David Dunlap’s work seems to be gently calling us to look beyond our limited view of what art could be about and towards something larger, more wholesome and inclusive–and possibly more fun!–than the self-preoccupation and blustery careerism of much contemporary art.

Equanimity means recognition of our interdependence: our lives do not unfold in a vacuum, but in a context of relationships. The poet Allen Ginsberg once wrote, “Art’s not empty if it shows its own emptiness.” Empty here does not mean nihilistic and despairing, but rather that emptiness is always empty of something: empty of permanence, continuity and a solid, indestructible, independent self. Art, like life, is relational, in other words, and the artist’s production arises in interdependence with the environment that the artist works and lives in. David Dunlap seems to revel in this empty, selfless aspect of his work, often collaborating with others in the seemingly large, rich tapestry of relationships he has cultivated over the course of his life. “The Men’s Fylfot Cross Correspondence Club” is one such ongoing collaboration of drawings passed between friends, with shapes that mutate and change as each person adds something on to the accumulating imagery, like an ongoing musical jam-session happening on paper.

My only criticism of this exhibition is that it is not nearly large enough to encompass the entire scope of David’s work—indeed, the present (though wonderful) installation is really only a small, modular piece of a much larger, ongoing work in progress. The largest exhibit of Mr. Dunlap’s work that I have seen to date was at the Des Moines Art Center in 1989, an enormous multi-room installation with wall-paintings, timelines, furniture, and of course the artist’s books. While browsing through the beautiful, gem-like installation at CUE, I kept imagining what it would be like to fill one of the Whitney Museum’s floors with a full-scale exhibit of Mr. Dunlap’s work, or possibly the expansive Marron Atrium at MoMA.

One of the unfortunate drawbacks of life in the Big Apple is that New York City often has a myopic eye when it comes to appreciating the rich variety of art work that exists in our great country outside the city. The CUE Foundation and the Reeder Brothers deserve a warm thanks for bringing generous work like this to New York.

Additional Notes from the CUE Press Release:

“His materials of choice come from the everyday – clothes, notebooks, calendars, automobiles, even paint made from mixing walnuts and buckets of water. Yet, while the base components may imply simplicity, they are far from easy to digest. Containing the recordings of thoughts and memories like daily journal entries or logbooks, the work provokes a cryptic sense of voyeurism. Dunlap employs an elaborate and deeply personal symbology in all of his work, linking the seemingly mundane and the profound, the personal and the cultural, the historical and the present. An intimate mythology is generated through his unique lexicon used for documenting his life. Recurring symbols like Martin Luther King, swastikas, dates and flags are found throughout his work, constantly being reworked within new contexts of his own personal documentation. However, Dunlap does not stake sole claim on the work; as with many of the symbols used, all of his work is open to interpretation, redefinition and re-appropriation. Through the resulting installation the viewer is led to question their initial conceptions of these “stock” images, underlining the obstructiveness of readymade thought and ideas.”

Visit Harold’s Sketchbooks at www.haroldgraves.com