David Dunlap at CUE Art Foundation

Friday, January 8th, 2010Note: please click on an image to view a larger photo, then click that photo to get even larger:

Notes on David Dunlap at CUE

The CUE Foundation is showing the protean work of Iowa City artist David Dunlap in their Chelsea gallery on west 25th street. This is an installation by an important and influential artist who has been deserving of larger recognition, at least in the New York art community, for a long while.

For the past four decades artist David Dunlap has been keeping a series of daily notebook journals and sketchbooks–a kind of stream-of-consciousness diary of daily life and reflections on art and the world, which he presents in various formats, each one showcasing a different incarnation of the artist’s ongoing work.

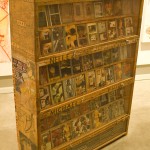

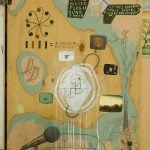

Empty, luminous, dream-like, ungraspable and mysterious: the current exhibition, Mr. Dunlap’s first solo show in New York City, has as its centerpiece a section of a fifty-foot high plywood house the artist constructed in his back yard in Iowa City. Inside and around the “house” are numerous hand-made book-cases displaying the many notebooks, sketchbooks and project-scrapbooks that have continued to accumulate like deposits in an ever-expanding coral reef of memories, dreams and doodles. In the middle of the house is an enigromatic object: A Device for Detecting the Presence of Martin Luther King, Jr. Along the walls of the exhibition space are displayed individual, framed drawings–many of them small pages pulled from the ubiquitous wire-bound notebooks Mr. Dunlap carries with him, while others are larger-format drawings, often executed with a ball-point pen: homemade calendars illustrated with abstract doodles and mysterious shapes. Most any mundane, ordinary event becomes the jumping-0ff point for long, meandering riffs on various fantastic and often funny drawings–abstract patterns that morph into figures and symbols which populate the daily calendar of a life lived with friends and family. Enigmatic phrases headline and punctuate the sprawling installation of imagery: Dreaming, He is At Work, Hitler Dream Analysis, Give Us Back Our Flag You Waterboarded, This is Always Finished, Free Art School!

Egolessness and equanimity are seemingly rare in our world, and this is particularly true in the New York “Art World” where egos are often large and tending towards the loud and self-important. The spirit of David Dunlap’s work seems to be gently calling us to look beyond our limited view of what art could be about and towards something larger, more wholesome and inclusive–and possibly more fun!–than the self-preoccupation and blustery careerism of much contemporary art.

Equanimity means recognition of our interdependence: our lives do not unfold in a vacuum, but in a context of relationships. The poet Allen Ginsberg once wrote, “Art’s not empty if it shows its own emptiness.” Empty here does not mean nihilistic and despairing, but rather that emptiness is always empty of something: empty of permanence, continuity and a solid, indestructible, independent self. Art, like life, is relational, in other words, and the artist’s production arises in interdependence with the environment that the artist works and lives in. David Dunlap seems to revel in this empty, selfless aspect of his work, often collaborating with others in the seemingly large, rich tapestry of relationships he has cultivated over the course of his life. “The Men’s Fylfot Cross Correspondence Club” is one such ongoing collaboration of drawings passed between friends, with shapes that mutate and change as each person adds something on to the accumulating imagery, like an ongoing musical jam-session happening on paper.

My only criticism of this exhibition is that it is not nearly large enough to encompass the entire scope of David’s work—indeed, the present (though wonderful) installation is really only a small, modular piece of a much larger, ongoing work in progress. The largest exhibit of Mr. Dunlap’s work that I have seen to date was at the Des Moines Art Center in 1989, an enormous multi-room installation with wall-paintings, timelines, furniture, and of course the artist’s books. While browsing through the beautiful, gem-like installation at CUE, I kept imagining what it would be like to fill one of the Whitney Museum’s floors with a full-scale exhibit of Mr. Dunlap’s work, or possibly the expansive Marron Atrium at MoMA.

One of the unfortunate drawbacks of life in the Big Apple is that New York City often has a myopic eye when it comes to appreciating the rich variety of art work that exists in our great country outside the city. The CUE Foundation and the Reeder Brothers deserve a warm thanks for bringing generous work like this to New York.

Additional Notes from the CUE Press Release:

“His materials of choice come from the everyday – clothes, notebooks, calendars, automobiles, even paint made from mixing walnuts and buckets of water. Yet, while the base components may imply simplicity, they are far from easy to digest. Containing the recordings of thoughts and memories like daily journal entries or logbooks, the work provokes a cryptic sense of voyeurism. Dunlap employs an elaborate and deeply personal symbology in all of his work, linking the seemingly mundane and the profound, the personal and the cultural, the historical and the present. An intimate mythology is generated through his unique lexicon used for documenting his life. Recurring symbols like Martin Luther King, swastikas, dates and flags are found throughout his work, constantly being reworked within new contexts of his own personal documentation. However, Dunlap does not stake sole claim on the work; as with many of the symbols used, all of his work is open to interpretation, redefinition and re-appropriation. Through the resulting installation the viewer is led to question their initial conceptions of these “stock” images, underlining the obstructiveness of readymade thought and ideas.”

Visit Harold’s Sketchbooks at www.haroldgraves.com