“The whole visible universe is only a storehouse of images and signs to which the imagination assigns a place and a relative value; it is a kind of nourishment that the imagination must digest and transform.”

“Nature is a temple in which living columns sometimes emit confused words. Man approaches it through forests of symbols, which observe him with familiar glances.”

—Charles Baudelaire

Symbolism, both as a movement in poetry as well as painting, is often said to have its source in Baudelaire’s writings. I suppose one could argue that this notion is a bit of inherited, modern European chauvinism, and that one might just as easily trace the origins of all symbolic expression to the cave paintings and petroglyphs of Cro-Magnon people living in the Dordogne 40,000 years ago. But for the purpose of reflecting on contemporary painting practice as it happens now, Baudelaire is just as good a jumping-off point as any. Depending on what historical scheme you want to follow, after Baudelaire comes Stéphane Mallarmé, then Paul Gaugin, and from there the trail branches off into a wilderness of groups, movements and characters, all clamoring for their place in the modern story of poetry and painting, in all its manifold expressions.

Nearly a century and a half separates us from Baudelaire now, and the forest of images has grown up around us, a vast expanse of confusion and promise. Where do these images arise from, and where do they go? The Romantic poets and their Symbolist heirs asked this question, and in their attempts to answer they gave the world Van Gogh and Gaugin, Wagner, Nietzsche, and Freud. When the Dadaists asked these questions they gave rise to Surrealism. Perhaps it was Warhol who joked that when late twentieth-century modernism asks these questions, they get the internet, along with a raft of corporate logos and advertising as a response; but Andy Warhol died before the internet came into being, so it probably wasn’t him. Compared to Baudelaire’s Paris, or the Dadaist’s Zurich, the 21st century metropolis is a whirlpool of commercial images in constant, swirling motion. Be that as it may, it seems as if the post-modern art spirit continues to ask, Where do we come from? What are we? Where are we going? Even when it seems that the only answers coming back are network sound-bites, YouTube clips and corporate pornography, the questions persist.

∞

The Bruce High Quality Foundation’s installation at the Whitney Biennial, We Like America, and America Likes Us is a darkly humorous elegy for a culture that is so deep in decline it appears to be coming apart at the seams. A white Cadillac ambulance is parked on the fourth floor of the Whitney in a room by itself, headlights shining against a blank wall, white curtains drawn over the rear windows, the driver’s side and passenger windows painted black. On the windshield, from somewhere inside the vehicle, a continuous looped video is projected, so that the ambulance has been transformed into a kind of movie theater. The video is a long montage of YouTube clips from familiar film and television broadcasts, presented in a documentary style, as if Ken Burns were giving an overview of late twentieth-century culture in a series of short snippets.

The framing device of the ambulance itself is actually where the video loop begins: a scene from Joseph Beuys’ important 1974 performance, the sardonically titled I Like America, and America Likes Me. Beuys arrives at JFK airport wearing his iconic felt fedora and fishing vest, disembarking from the plane with his hand covering his eyes; he is met by a pair of assistants who immediately wrap him in a gray felt blanket and load him into the back of a Cadillac Miller-Meteor ambulance, almost identical to the one sitting in the museum. We then see the white vehicle, with lights flashing, rushing through traffic to arrive at the René Block gallery in Manhattan, where Beuys will spend the next several days alone in a room with a coyote—an animal of symbolic importance in much of Native American mythology.

Beuys’ performance has been discussed at length elsewhere, so I will just mention here that after establishing some rapport with the animal over 3 days he embraced the coyote and then left New York City the same way that he arrived, being carried to JFK in the back of the ambulance, later explaining “I wanted to isolate myself, insulate myself, see nothing of America other than the coyote.” It happens that the Cadillac Miller-Meteor ambulance is also commonly used as a hearse, and this dual function of the vehicle forms part of the poetic irony of the Bruce installation; a female voice narrates a long, rambling, narrative-poem in which America is eulogized as a person who has recently died, or perhaps a lover or spouse who has been separated. The ambulance that carried Joseph Beuys to commune with the Native Spirit of America has now become a hearse, presumably with the dead corpse of America lying concealed in the back, the ghost of our collective fantasies about “America” flickering on the windshield in a late-night television rerun with the sound turned off. For me, We Like America, and America Likes Us is the most potent piece in this year’s Biennial; in it’s satiric way it establishes a theme that runs throughout the rest of the exhibits; even the choice of having a female narrator for the voiceover seems significant, as much of the strongest work in the rest of the show is by women.

∞

So here is my list of notables from the Whitney Biennial: the Bruce High Quality Foundation is a collective of anonymous artists, each of them named “Bruce;” after that, Nina Berman, Dawn Clements, Hannah Greely, Josephine Meckseper, Erika Vogt, Sharon Hayes, Aurel Schmidt, Kate Gilmore, Maureen Gallace, and Julia Fish, in no particular order. Four video artists, two painters, two drafts-women, a sculptor and a photographer, plus the Bruce installation.

Josephine Meckseper’s video, Mall of America, continues the critique of American cultural identities—a long, slow-motion video shot with color filters in a large, sprawling shopping mall, with an ominous, droning soundtrack. The combination of slow-motion, saturated color and menacing ambient sound transforms the commonplace environment of a suburban shopping center into a nightmarish underworld. In one sequence a Hollywood war movie is playing on a flat-screen TV behind a glass display case, and the camera zooms in until we are momentarily “inside” the movie which is playing inside the Mall—a simple but effective way to conflate the theater of “actual” warfare with Hollywood and the pervasive consumer culture that the Mall-space represents.

Kate Gilmore’s Standing Here is a claustrophobic video installation: watching the artist punch and kick her way out of the narrow confinement of a sheet-rock cubicle is made more visceral by the fact that the actual space she shot the video in is right there in the room, next to where the video is being projected. As I was standing there watching Gilmore—who is wearing a red dress with white polka-dots—kick and tear at the confining walls, I heard several of the people with me remark how uptight and claustrophobic it made them feel. The gray, silo-like cube is of course intended to be metaphoric of repressive patriarchal structures that confine and challenge women—but I suppose it could also be symbolic of forces or ideas that can confine and limit any of us, whether those forces be patriarchal, political, aesthetic, or even “feminist.”

∞

-

-

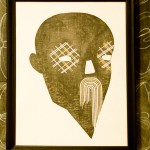

“Angel T” by Tourya Othman

-

-

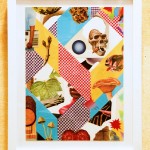

“Sacre (Homage to Michelangelo Galliani)” by Michela Martello

-

-

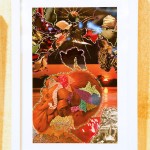

“Courage (detail)” by Michela Martello

-

-

“Cuore” by Michela Martello

-

-

-

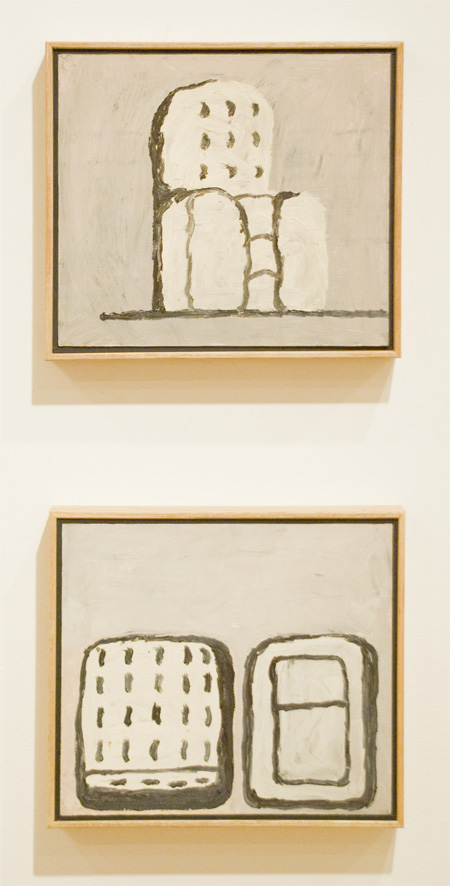

“Last One” by Michela Martello

-

-

“Venus” by Michela Martello

-

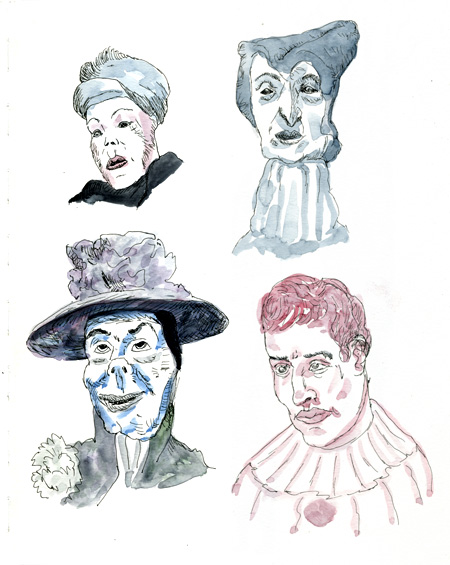

Michela Martello and Tourya Othman are two artists currently exhibiting at the Tria gallery, in a show entitled Idols and Icons. Working in a symbolist mode of representation, both artists create paintings derived from the imagery of traditional religious and spiritual iconography. Othman’s paintings of cherubic “angel heads” put one in mind of the Baroque paintings of Georges de la Tour with their open-mouthed depictions of ecstatic rapture and numinous awe in bold chiaroscuro—but with the introduction of a surreal chromatic intensity that is reminiscent of the Chicago Imagist painter Ed Paschke, or even some of the later, hallucinogenic realism of Salvador Dali.

Martello’s five canvases draw on historical, religious imagery from both Eastern and Western culture to create a personal symbolism—images of Italian sculpture and Latin American folk art as well as Hindu and Buddhist depictions of bodhisattva-like figures. There’s a certain lightness of touch and handling of paint that reminds me of recent fresco paintings by Francesco Clemente. But the personal symbolism and feminine concern with identity also makes one think of Frida Kahlo or Leonora Carrington—two artists whose work is in the spirit of Baudelaire’s Symbolist ideas. Courage features the truncated form of a standing warrior brandishing a sword in the manner of a Hindu or Buddhist ceremonial court figure, while the kilt worn by the bodhisattva-like guardian has numerous nude female figures painted on it, each of them situated in various states of repose upon a pink field. The alluring, relaxed eroticism of the small dakini-like women combined with the masculine solidity and strength of the sword-wielding figure is a compelling combination of opposites.

Perhaps it is appropriate that Cuore, a small square painting of a red heart with the aorta severed and a small yellow tiger standing in the middle, is situated on a blue field directly above Courage. The courage and open-heartedness that is required to be an artist in a world obsessed with confining formalist structures, as Kate Gilmore seems to be suggesting in her work at the Whitney? Or, perhaps more specifically the courage to be a female artist in a milieu that is traditionally dominated by men. I think Martello is too intelligent of an artist to allow herself to be confined to any one of these meanings. A friend who is deeply involved with esoteric Buddhist practices has suggested that the image could simply be evoking the courage to remain an open human being, working with the forms that one has inherited from one’s culture while remaining free from their limitations. In any case, Cuore with it’s little tiger in the center and the suggestion of gratitude as an antidote for anger and greed is possibly my favorite painting in the show, along with Last One, a painting of fifteen miniature Christmas decorations that the artist sketched while traveling in Ecuador. This is the painting that most puts me in mind of Clemente with its lightness of touch, gentle naiveté, and suggestion of mystical portents. Each figure is delicately rendered, as in an old illustrated catalog of children’s toys, and is floating against a seemingly empty field of raw canvas. As in the best of Clemente’s work, there is a mystery in the presence of the figures that escapes explanation.

∞

“No ideas but in things.”—William Carlos Williams

As I was preparing to work on this entry, an advance copy of Christopher Sunset, the new book of poetry by Geoffrey Nutter, arrived in the mail. Mr. Nutter is one of those rare poets who, like John Ash or Pablo Neruda, is possessed of a genius that simultaneously opens out towards a field of mystical imagery—laden with the possibility of transcendence—while remaining firmly grounded in the matter-of-fact, stubborn currency of the everyday, the here-and-now.

A poem by Mr. Nutter entitled Thanksgiving declares:

I’ve been puzzled long enough

by modernity and its poems.

It’s evening. I’m walking down

to the river to watch the sun set.

The clouds are like millions of bright blue leaves

scattered across the sky.

I’m sitting in the shade of a massive tree

but the shade is alive. And under the sunset

the giant gray trestles of the bridge.

And under the bridge, and nearer to me,

shards of bottles and the gravel

of the down-at-the-heels marina,

its broken-down boathouse, the gray

cinder blocks in the weeds, an overturned

boat, a length of black tubing.

It’s all coming together now.

It’s the sky and the earth, resting together

in the unassuming darkness.

—Thanksgiving, from Christopher Sunset, ©2010 by Geoffrey Nutter, published by Wave Books

∞

Visit my website at www.haroldgraves.com